A Brief History of Civilian Internment in the Far East, World War II

On 7 December 1941, the Japanese attacked the American fleet at Pearl Harbor; the following one hundred days were cataclysmic moments in the lives of the Western colonial communities in the Far East.

British and colonial military and volunteer forces fought bravely during that war in the Far East, many losing their lives during the battles. Upon surrender approximately 132,000 Allied military survivors found themselves captured and interned by the Japanese in a variety of different POW camps across the Far East. Almost 25% of the Far Eastern POWs died in captivity.

These deaths and terrible suffering, especially of those working on the Burma and Thailand railways, have been the subject of much historical and media coverage and no right thinking person would want to forget or diminish those heroic, male, military stories.

It should also be remembered, however, that an estimated 130,000 Allied civilians: approximately 51,700 men, 40,000 children and 42,000 women were also captured and interned in a variety of camps in many different locations in the Far East by the Japanese during the same period.

The Japanese had no policy for the treatment of enemy civilian Internees. Nevertheless, research shows that from their initial victory over the Western Allies in December 1941 to their surrender in August 1945, the Japanese created hundreds of civilian internment camps in Japan, Korea, Manchuria, China, French Indo China, Thailand, Hong Kong, Republic of the Philippines, Burma, Singapore, Sumatra, Java, West Borneo, East Borneo, and the Celebes. The camps themselves differed enormously. The smallest camp, Pangkalpinang in Sumatra, held approximately four people. The largest, Tjihapit I in Java, held around 14,000. In some areas, mainly Java and Sumatra, the men were separated from the women and children and, from about 1944 onwards, boys over ten years of age (the age differed over time and place) were transferred from the women’s camps to the men’s camps. In Java there were special camps for boys, the sick, and old men. In other areas, particularly China and Hong Kong, men, women and children shared the camp accommodation. Some internees remained in the same camp throughout internment, others, particularly those in Java and Sumatra, were moved from camp to camp several times. Accommodation differed from area to area with the Japanese using a variety of schools, warehouses, university buildings, prisons, houses or bamboo barracks.

As for the women specifically, over 3,000 were interned in camps in China, nearly 1,000 in Hong Kong, just over 1,000 in Singapore and over 2,000 in the American colonised Philippines. However, by far the largest group of women were the 29,000 predominantly Dutch women and their 33,000 children who were captured and interned in camps in Java and Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). A number of British women and children, along with Australian nurses and other nationalities were also captured in the Dutch East Indies after their ships were attacked during their belated evacuation attempts from Singapore.

In China and Hong Kong the women were in mixed camps with the men and children. In Singapore the women shared Changi Prison with the men but were segregated from them. In Santo Tomas in the Philippines, the men and women had separate dormitories but they lived communally during the day. In Java and Sumatra all the camps were sexually segregated with male and female survivors only meeting again after the war.

Although the women in the mixed camps re-entered a male dominated world they were conscious of the fragility of their internment existence. They acknowledged how dependent they were on the skills of the men and the need to work in partnership for physical and psychological survival. The women gardened, cooked, taught, nursed, cleaned rooms and vegetables, did mending and “doled out drinking water for hours, daily, in all weathers.” (1)

The web of support offered by the women in the mixed camps was highly significant and should never be underestimated. Their practical skills, hard work, creativity and caring helped all the internees both physically and psychologically.

For the women caught in Java and Sumatra, the totally female internment camp was, for a variety of reasons, a desolate landscape to come to terms with. The lack of evacuation prior to the Japanese attacks meant that not only were thousands of women captured by the Japanese but also thousands of young children. Unlike the women in the mixed camps, they had no access to trained administrators, engineers, carpenters and chemists. Consequently it was impossible to ensure basic public utilities were created and maintained at a sanitary level. Having no male doctors and only a few female doctors in their midst they also had less access to medical care. In a camp of 4,000 women in Java there were only three doctors to attend to the internees. In addition, whether sick or not, the Japanese forced these women to carry out hard manual labour. They were also subjected to severe discipline not suffered by the women in the mixed camps, and a relative few were used as ‘comfort’ women to Japanese officers.

Rarely did the women remain in one camp and the sudden and unexpected moves from camp to camp scared them, it fragmented families and support groups and often the women’s limited equipment had to be left behind. Internee, Daphne Jackson, recorded:

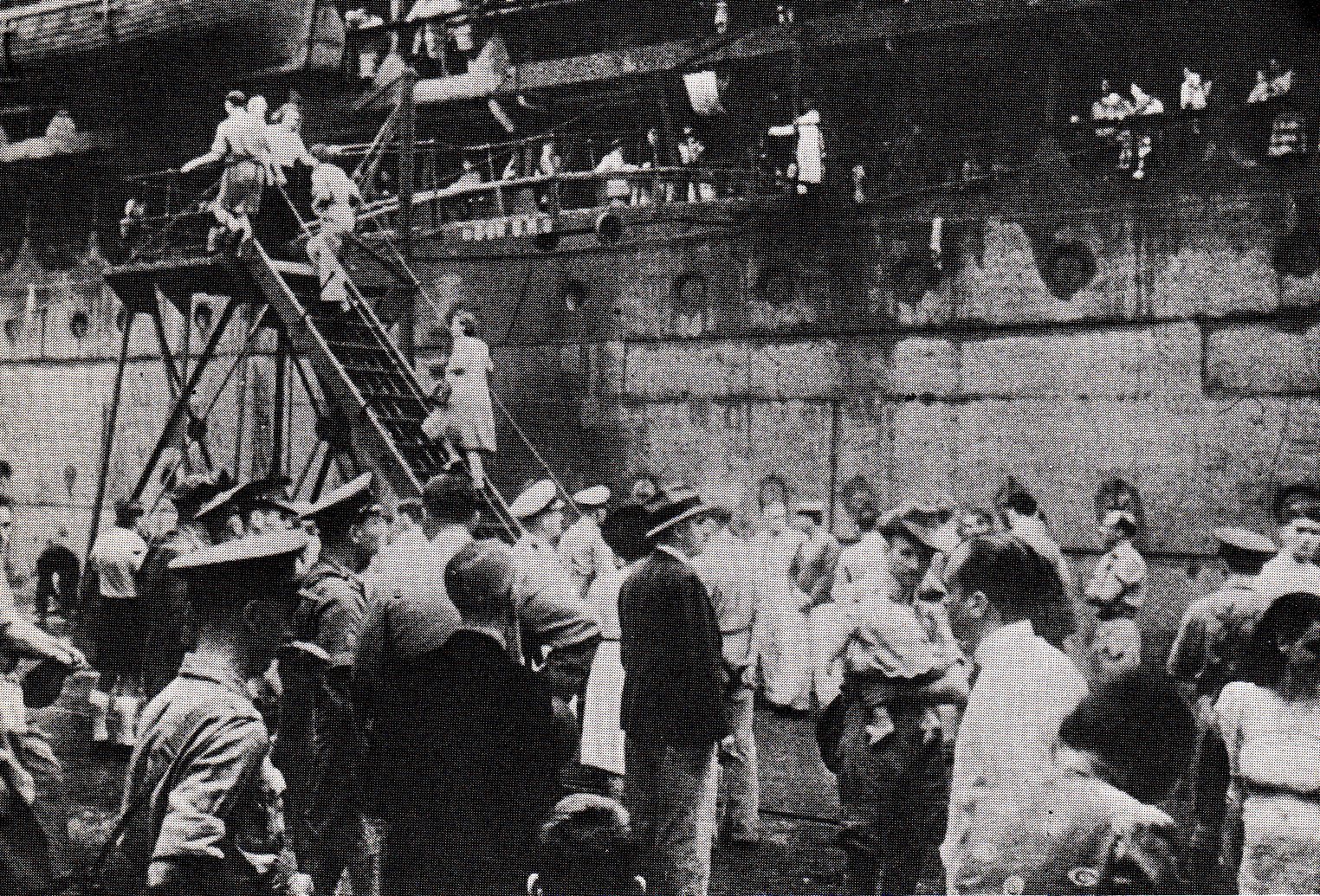

‘At about two-thirty we moved out of the prison – a most pitiable collection of humanity, covered with ulcers on arms and legs on which the flies settled, and laden with bits of luggage, tins, buckets, and bags,for by this time we had learned to hang on like grim death to any nail, tin or bit of string.’ (2)

The journeys themselves, either walking or in cramped trucks, trains or boats, aggravated health problems, and sometimes they were fatal. Consequently, these women were in perpetual fear for their own and their children’s safety and survival.

In spite of this, these women demonstrated that they were able to organise the camps; they were the labour force, the furniture movers, the navvies, the gardeners, cooks, latrine clearers and child carers. They nursed the sick and buried the dead. Yet they were prepared to use physical force or subtle forms of resistance if they were threatened. When dehumanised or de-feminised by discipline or hard work, they found ways to re-humanise and re-feminise themselves and found subtle ways to defy the Japanese attempts to destroy their humanity, femininity and morale.

Internment at Palembang and the Vocal Orchestra

Fleeing just days, and in some case hours before the Fall of Singapore, British women and children were among the thousands of many nationalities that boarded ships in a desperate attempt to get away to safety.

Sadly many were to die as their ships were attacked and sunk only hours out of port, either from wounds sustained from the attack, or from drowning. Of those who survived the bombing many found themselves, after days at sea, on the shores of Banka Island just off the coast of Sumatra.

As they were taken into captivity they were met by others who had shared the same fate as well as those whose ship, the Mata Hari, had been captured. This ship had carried Margaret Dryburgh, her three fellow missionaries, Phyllis Briggs and Mamie Colley who were all to become members of Garage 9; it is here the story of the Palembang Women’s Internment Camp and the Vocal Orchestra begins.

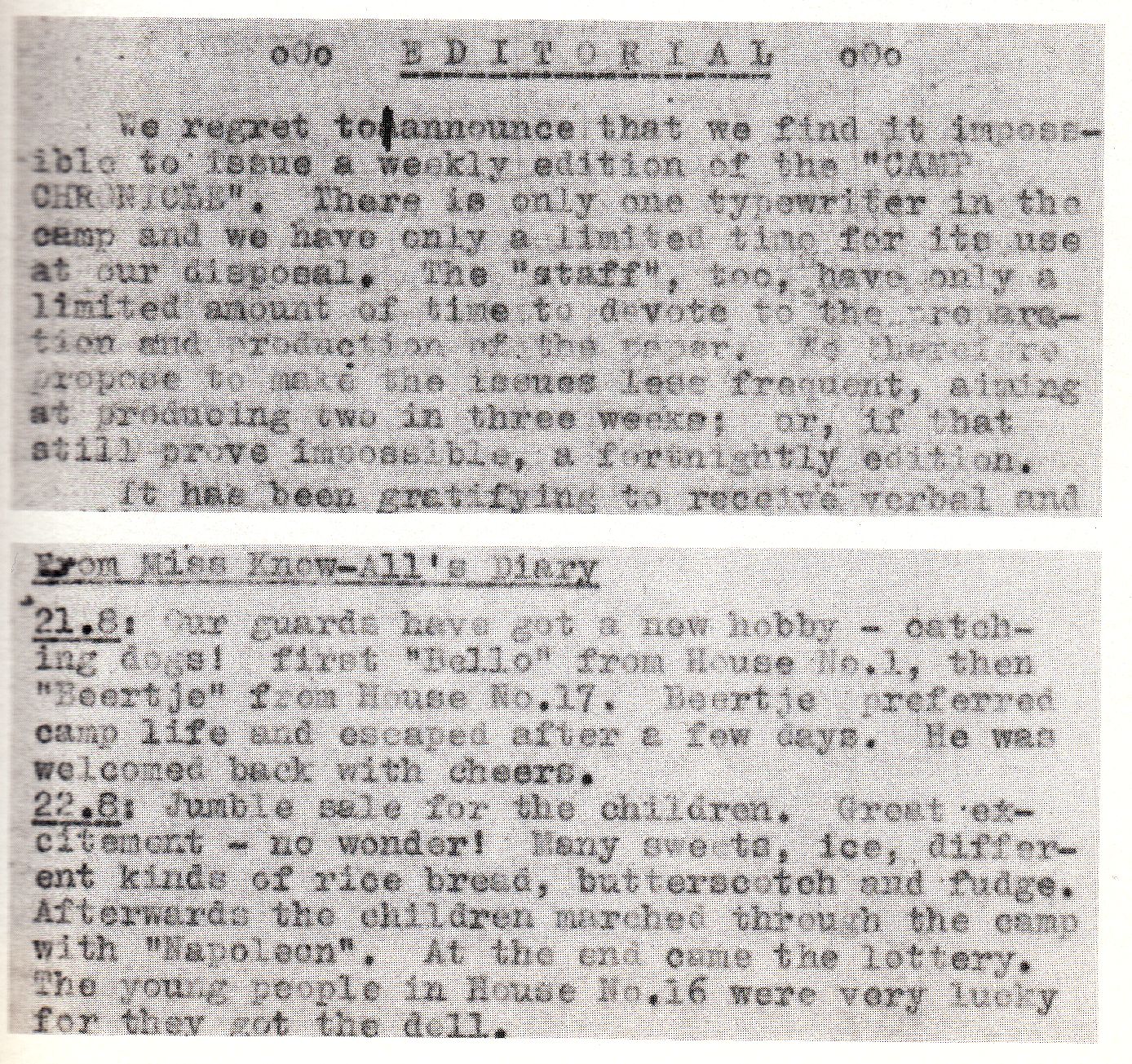

Following the move from their original internment in Muntok, on Banka Island, a journey of two days, they were housed in small Dutch bungalows, only to be moved again in less than one month to bungalows in a different area of Palembang. As women crowded into these bungalows in Irenelaan only a garage, ‘Garage 9’ remained for a group who had somehow found themselves together including Shelagh Brown and her mother Mary who had survived days at sea; fifteen were to make their home there for eighteen months. Upon reflection years later their time at the ‘bungalows camp’ was considered to be a time of much activity and at times humour, as the many clubs, talks, drama productions, choral societies and twice monthly ‘Camp Chronicle’ (below right) occupied their time.

The women of Palembang had utilised their skills and talents in an effort to maintain a civilised society, ensuring that physical and mental abilities were considered in tasks allocated. Several had, surprisingly, voiced their delight at mastering a new skill, but perhaps the most amazing achievement was the ‘vocal orchestra’.

The women had been moved to the Palembang barracks camp, known as the ‘Men’s Camp’, in September 1943. This was their third move and was to mark a sharp decline in accommodation, health and food.The move to the ‘Men’s Camp’ in Palembang was made even worse as the men, believing that their ‘barracks camp’ was to be used by the Japanese, had deliberately left it in a filthy state. Margot Turner a QA nurse and later to become Brigadier Dame Margot Turner, returned to the camp just days after this move. She and three other nurses who, for no apparent reason, had been imprisoned for six months wrote:

‘…the new camp had been constructed on swampy ground below sea level and it was thick with bugs, rats, fleas and mosquitoes’. (3)

The wooden barrack-like buildings were windowless and rain consistently seeped through the palm thatch onto the boards below where the women and children slept. The entire camp was only a hundred yards long by about forty yards wide, Shelagh Brown wrote in her diary:

‘…terrific rain and roofs leak and compound is thick mud. Lots of colds and bad tummies still. There are 51 in our dormitory’. (4)

Unbelievably it was into this environment, just a short time after moving that the idea of the ‘vocal orchestra’ was born. Hunger, disease, squalor and hard manual labour had curtailed many of the entertainment activities; along with overcrowding and a growing assortment of nationalities, friction was bound to erupt. Not only was it an inspirational idea but Norah Chambers and Margaret Dryburgh were able to rise above the squalor, disease and hunger to bring something of beauty and joy to the entire camp. Read a full history of the Vocal Orchestra here.

When the concert was performed on December 27th many of the audience wept, they had not expected such beauty amid the hunger, bedbugs, rats and filth that had come to characterise their lives. Margot Turner remarked that:

‘…it was the most wonderful thing in our lives and I don’t know what we should have done without it’. (5)

These occasional concerts continued for more than a year, ceasing eventually as nineteen of the thirty-strong orchestra died. They were to be moved yet again in November 1944 back to Muntok on Banka Island where so many died not only from starvation, malaria and dysentery, but from an illness marked by a raging fever, followed by unconsciousness and a skin reaction; this combination of symptoms was named ‘Banka fever,’ and more women were to die here than any other camp.

The final move was to Loebuk Linggau deep into the heartland of Sumatra, a shocking journey that took 4 days and claimed the lives of many, either on the way, or shortly after arriving on the 9th April 1945. Margaret Dryburgh died on 21st April 1945 with Norah Chambers at her side. Norah said after the war that she had learnt a lot from Margaret and that she had made a difference to her life. Together these two women had achieved something remarkable and a lasting legacy to their determination and fortitude in such appalling conditions, unimaginable to us today.

The 70th anniversary Vocal Orchestra concert in Chichester not only celebrates the women involved in that original vocal orchestra but it also pays tribute to all the civilian men, women and children who were captured in the Far East during World War II and also the terrible price paid by many of the military personnel who fought to defend them.

Authors: Dr.Bernice Archer & Barbara Coombes

References

1. Abkhazi, Peggy, 1995, ‘Enemy Subject’: Life in a Japanese Internment Camp 1943–45, 2nd ed. (Stroud: Alan Hutton Publishing) pp. 53 & 62.

2. Jackson, Daphne, 1989, Java Nightmare (Padstow: Grafton Books) p 67.

3. Smyth, J. Sir, 1986, The Story of Dame Margot Turner (Leicestershire: Thorpe Publishing) p 88.

4. Brown, Shelagh, Private Diary: Imperial War Museum.

5. As 3. above, p 91.

Statistics referred to are mainly from: Velden, Dr D. Van, De Japanse Interneringskampen Voor Burgers Gedurende de Tweede Wereldoorlog – Japanese Civil Internment Camps During the Second World War (Groningen: J.B. Wolters, 1963)